This page was last updated May 15, 2012

Send questions and comments here.

The Quest For

Fair Fares

in the GTHA

Contents

What is an equitable way to charge public transit fares?

Public transit costs money to operate and this is covered through a combination of fare box revenues and tax subsidy. The percentage of how much each of these contributes can vary from one transit operator to the next. When a passenger needs to travel from an area served by one operator to an area served by another, they often have to pay two completely separate fares. This jump in transit cost to the user, simply because a border was crossed, can often be a deterrent to using public transit.

Some might argue that as a public service, transit should be free for the user. That would mean that the operating cost would be covered fully by taxes and there would be no fare for the user to pay. While that would be nice, and would simplify matters for trips involving different operators, there tends to be problems when the user loses the sense of value that is instilled by paying a fare (user fee). That is to say that users are more likely to take action about planned service cuts when this sense of value exists compared to when cuts are made to services that involve no direct out-of-pocket cost to the user. While that is a debatable point, this page will work with the assumption that there will continue to be fares for public transit in the GTHA.

Fare By Distance System?

Some argue that people should pay for what they use. For transit, this tends to mean a "fare by distance" system, such as what GO Transit uses. This has three drawbacks:

- Instead of actually charging for the actual distance proportionately, zones are used. The more zones one travels through, the higher the fare. This means that often multiple stops are in the same zone, and in turn means that one more stop might cost more, but one less stop might cost the same.

- Longer distance commuters may be discouraged from using transit due to the increased cost. These are the very commuters that should be encouraged to use transit. Since their longer commute often adds more stops to their trip, the increased cost is in both money and time. The costs of driving and parking becomes attractive due of this.

- Short distance commuters may be discouraged to use a system when the fare by distance involves a base fare plus zone charges and the transit agency chooses to increase fares by raising the base fare that applies to everyone.

In the past few years, GO Transit commuters found this out when the base fare was raised (e.g.: 25 cents on March 16, 2009). Over the previous four years, a commuter traveling from Old Cummer (near Leslie and Finch) to Union had experienced fare increases of 27%, while longer distance commuters have had lower percentage increases (9% for Barrie, 14% for Oshawa, and 10% for Hamilton).A system that has features that discourages both long distance and short distance commuters is seriously flawed!

Flat Fare?

Until 1973, the TTC had two zones within Metropolitan Toronto (what is now the City of Toronto). Since that time, all of Toronto became a single zone, allowing one to make a trip for a single fare, regardless of its length, as long as it was within Toronto.

While a single flat fare makes transit more attractive for longer distance commuters, it leaves short distance and even medium distance commuters feeling that their fare is subsidizing the long distance commuters.

Somewhere between these two extremes lies a system that has the best chance of making most commuters feel they are getting a good value for their money!

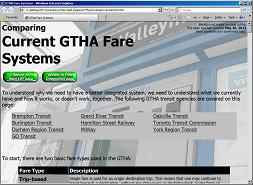

What currently exists in the GTHA?

Click on the thumnail image of the GTHA Fare System page to the right to take a look and compare fares and integration efforts across the GTHA.

That will give you the details, but the simple fact is that when you move from one operator's territory to another's, you pay an entire new fare. The exceptions to this are:

- Special "ride to GO" type fares, where available.

- Some neighbouring agencies accept the other's passes at connection points.

- Many GTHA agencies accept each other's valid transfers. Though, the TTC does not participate in this and in many cases travel involving two agencies that accept each other's transfers will require a connection on the TTC.

- Transfer privileges to and from GO bus operations in Durham Region with DRT.

- TTC routes that operate outside of Toronto are a contracted bus for the other agency while outside Toronto; full transfer privileges exist, but if the bus is boarded while in Toronto, the fare for the other agency must be paid to receive a transfer punched for the other agency; when going into Toronto, the TTC fare must be paid in addition to the fare of the other agency.

This basically means that the GTHA as a whole is a zone-base fare-by-distance system. Unlike GO Transit, where the fare is based on a base rate plus a distance charge based on the zones one travels between, transit riders using other operators must pay an entire new base fare when a fare boundary is crossed. This means that a person with a 4 km commute that crosses a border pays double, while the person with a 40 km commute within the territory of one operator pays a single fare. This is not exactly what one would call fare by distance!

There is also a non-symmetrical treatment of borders when the TTC is involved. When the TTC crosses outside of Toronto, it acts as a contractor for the other agency, and must collect their fare. When one boards a TTC bus while in Toronto, they pay the TTC fare. When it crosses the border and becomes a bus for the other agency, the passenger must pay the other agency's fare when they leave. However, if they need a transfer, the TTC operator will punch it to indicate that the other fare has been paid. The transfer may be used to board a bus operated by the other agency. If the passenger boards the TTC bus outside of Toronto, they will only have to pay the fare of the other agency. This fare is usually collected when leaving if the bus is traveling away from Toronto, or when boarding when traveling on the return trip. On a return trip, a passenger boarding need only pay the other agency's fare (or show a pass or valid transfer) to board provided they don't cross the border. If they are traveling into Toronto, they will also have to pay the TTC fare.

There are some routes of other agencies that operate into Toronto. These routes do not collect the TTC fare when the border is crossed. There are no transfer privileges with TTC routes. Additionally, when heading into Toronto, these routes are only permitted to drop off passengers, while on the return trip these routes are only permitted to pick up passengers while still in Toronto.

As an example, prior to the fall of 2010, if one had to travel from the intersection of Highway 7 and Leslie Street (in York Region) to Fairview Mall (at Don Mills and Sheppard in Toronto), on a weekday there were two bus routes to choose from. One was TTC's route 25D, but as a contracted service riders must pay the YRT fare and the TTC fare for a total of $6.25 (at that time) each way! The other choice was YRT's route 90, which cost only $3.25 each way (at that time, but YRT also uses a time-based transfer, so if the return trip is within 2 hours, only $3.25 would have been needed for the whole trip).

Clearly, there is a problem. At best, this problem is unfair to transit users, at worst, it is a deterrent to using public transit.

Who will pay for Fare Integration?

Before outlining a system of fare integration, let us discuss the cost. We are talking about reducing or eliminating the payment of extra fares when a trip involves more than one transit operator. This loss of fare-box revenue must be made up somewhere.

One source could be to raise the base fare for all operators, but this would likely be seen as getting short-distance users to subsidize longer distance users. There may have to be some small adjustments, likely upwards, as an integrated fare system would be most easily implemented if all agencies involved charged the same base fare.

That said, an integrated fare structure would not preclude an individual operator from offering a special local-only fare (see "City Saver" fares below) at a reduced cost.

The other source of paying for an integrated fare system would be for the province to cover the cost. Given that inter-agency transportation covers a wider area, and that a major alternative is increased use of the provincial highway network, it would seem reasonable that this cost should be covered by the provincial government. An ongoing, sustained level of provincial funding to cover some of the operational costs of all transit agencies should be a responsibility of the provincial government, but that is a whole other discussion.

The Fare Integration Plan

Remember, this is a possible proposal. It is open to debate, criticism, and from that, amendments. Feel free to comment on this blog page.

The goal of this plan is an equitable fare system that encourages long distance commuters while not leaving short distance commuters feeling they are subsidizing the other.

This plan is not suggesting the elimination separate transit agencies, nor is it suggesting having one huge flat fare for all of the GTHA. Local agencies tend to know local needs better, and can operate the service to meet those needs.

At the same time, the plan attempts to "smooth out" the transition between operators with an equitable fare system that provides full transfer privileges between different operators. It should not matter who a fare is paid to, if the fare applies to the zones involved, the transfer should be accepted on any other transit vehicle traveling within those zones.

This plan does not suggest introducing new zones by splitting any existing operator. It is assumed that each operator's region will be one zone (unless it is already more than one zone, such as in York Region). Some might suggest that the TTC should return to having two zones within Toronto, but that too is a whole other topic (which can be discussed in the blog).

1: Unified Fare Structure with Time-based Fares

Before any idea of integrating fares can move forward, all the transit agencies will have to adopt a unified fare structure. At the heart of this, is the move to a time-based transfer system for all agencies.

Gone are the days where a transit agency mainly exists to move people to and from work during weekday rush hours. Transit use is for many purposes, at many different times of the day. A high number of transit users now use monthly passes or, where available, weekly passes. The idea that a fare is paid for specific travel from a single origin to a single destination is history. When one's trip does not fit that model, one will use another mode of transportation.

The future is to look at paying a fare as purchasing a block of time usage of the transit facility. Most GTHA agencies have moved towards this time-based system, where a single cash fare or ticket gives the user up to two hours of transit use. Enter, leave, re-enter, go one direction, go the other direction - one can make use of the transit system in whatever way possible until the transfer or fare receipt expires. A single fare is simply a short-period pass.

This has the added benefit of eliminating most transfer-related fare disputes: if the time shown on the transfer has expired, the transfer is no good. There are no issues with where one uses the transfer, if one is going "the right way", or if one is carrying packages from a shop near the transfer point. There may also be a cost reduction for transfers, as there is no need to print separate transfers for each route.

2: Overlapping Boundaries

One of the biggest deterrents to using transit occurs when someone lives close to a boundary between operators. Most current situations involve paying a whole extra fare when the border is crossed. This often leads to people choosing to drive and park across the boundary to avoid paying the second fare. In some cases, the level of effort to drive and pay for parking can mean that some will drive all the way and not use transit at all.

No transit user who is only going a few stops wants to feel they are subsidizing someone traveling farther. This applies equally for someone using the Queen streetcar between Dufferin and Yonge Street as it does to the person using TTC Route 68B on Warden between McNicoll Avenue in Scarborough and Denison Street in Markham.

Instead of a single line that separates two zones, such as Steeles Avenue, two zones should overlap for a few kilometres. The amount of overlap is open for debate, but a good suggestion would be four kilometres. On Yonge Street, this would mean that the TTC zone would extend as far north as Centre Street, approximately two kilometres north of Steeles, and York Region's Zone 1 would extend as far south as Finch Avenue.

Anyone paying the base fare in the TTC's zone could travel as far north as Centre Street without having to pay extra. They would also have full transfer privileges onto any other transit vehicle operating in the same zone as the one where the fare was paid. Continuing one's travel into the other zone will require payment of a zone supplement, as will be discussed in the next section

Similarly, anyone paying the base fare in YRT's zone 1 could travel as far south as Finch Avenue without having to pay extra. This person would also have full transfer privileges onto any other transit vehicle operating in that same zone.

3: Zone Supplement Fares

When one's trip requires traveling into a different fare zone, a fare-by-distance model suggests they should be paying more for the trip. However, the transit user should not have to pay an entire separate fare. Instead, a supplement should be paid, for example, and additional dollar or two. The supplement could be paid when crossing fully into a new zone, or it could be paid at the start of travel, where a transfer could indicate the zones that the fare covers.

The issue of expiry time as it pertains to zone supplements may come into play. This is another debatable detail along with the amount of the zone supplement.

A trip that spans more than one zone will likely take longer, so it follows that a fare paid for more than one zone might have a longer expiry period. One line of thinking is that the expiry time should be extended an additional 30 minutes for each additional zone that is paid for. On the other hand, it is not as common for a longer multi-zone trip to be used for on-and-off, multi-point trips, so extra time may not likely be needed for the multi-zone traveler. Any trip that requires travel through more than three zones would likely be better served by GO Transit, which is described in the next section.

4: Full Integration with GO Transit

Over the next decade, much of GO Transit's operations will be transformed from a rush-hour only system to a full day frequent service operation. This will make GO a substantial component of GTHA and regional transit - a true viable alternative for other modes.

As such, it makes most sense to have its operation and fare structure be fully integrated with other transit agencies. GO fares should be set according to the GTHA-wide structure. This means that it would be the GTA base fare plus the appropriate number of zone supplements. This would also mean that any other transit vehicle used to get to or from a GO station would not cost any extra.

If traveling from a location in Newmarket to a location in Pickering, one could board a YRT vehicle, paying the base fare, to get to the GO station. At the GO station, three zone supplements could be paid to supplement the YRT transfer (one supplement for traveling between YRT zones 2 and 1, the second for traveling between YRT zone 1 and the TTC zone, and the third for traveling between the TTC zone and the DRT zone). Upon arrival in Pickering, there would be no additional cost to transfer to a DRT bus to reach the final destination.

Another debatable point is that GO tends to be a longer-haul, express-based service, and therefore should cost extra. Due to this, it is conceivable that the addition of a single supplement in addition to the rest of the fare calculation may be justified. This results in the user paying a slightly higher fare for the faster service, but not so much higher that it deters people from using GO where it is appropriate. Whether or not a GO fare is slightly higher than the normal fare between the two zones in question, GO's fare should include transfer privileges to all local routes in the zones at each end.

GO's current rush-hour tidal mode of operation fills their parking facilities leaving little room for any parking for all day service users. This makes full integration with local transit services even more important for the all-day operations than it does for rush hour.

5: "City Saver" (Local) Discount Fares

While it is conceivable that part of the cost of fare integration may have to be paid at the fare box by a slightly higher base fare, this can be slightly offset for short-distance users who only need to travel within a single zone with the use of a City Saver discount fare.

For example, if the base fare were to be $4, which gets the user 2 hours of travel within a single zone plus the ability to travel into additional zones with the addition of a zone supplement, a transit agency could offer a City Saver fare for a reduced cost with limitations on its usage. Perhaps for $2, a user could have 60 minutes of transit use on a single operator that cannot be upgraded to another zone.